Words elude me; they feel heavy and shallow. They drag themselves all the way from my mind but refuse to creep out of my lips, leaving a bitter taste on my tongue. My thoughts scatter, playing a relentless game of hide and seek with one another. I’m getting tired of this game, and my body feels crippled under the weight of it all. I recognize ennui✨, subtly hiding behind the veil of overload. When I am bored, I feel it throughout my entire body. Exhaustion and frustration take the wheel, hijacking my already timid motivation, and my thoughts take full advantage to roam free in insalubrious meanders.

How is it that boredom has this strange way of sneaking in and making life feel so overwhelming?

Andreas Elpidorou, a researcher in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Louisville explains, “Boredom is both a warning that we are not doing what we want to be doing and a “push” that motivates us to switch goals and projects.”

So, could it be that I’ve been ✌️unfairly✌️ cornering boredom all along, throwing all the accusations its way?

WHAT IS BOREDOM?

Boredom is the aversive state that we hit when our surroundings or activities fail to live up to our expectations, leaving us feeling hollow and questioning the point of everything.

Everyone experiences boredom, but how and where it happens depends on exogenous factors (like the situation), and endogenous factors (like our personality and expectations).

When we’re bored, we feel totally out of sync with reality and will do whatever is within our grasp to get back to an optimum state of stimulation, a state where we feel good and fulfilled.

But what if boredom was a wake-up call 📢 rather than just an agonizing, pointless experience?

WHY DO WE FEEL BORED?

Boredom is an emotion, and as Sandi Mann, psychologist and author of The Upside of Downtime: Why Boredom Is Good, puts it, “Every emotion has purpose — an evolutionary benefit.”

How is that, you say?

Well, one way to see this is by imagining living in a world where everything is endlessly exciting — even the small talk with your spit-spattering neighbor. Sounds exhausting, right? We’d have no clue what’s actually worth our attention. Turns out boredom is not a bug but a survival feature, nudging us to refocus when things get too dull (and spittery 💦).

Another way to see boredom is as a powerful tool for hunting down more mental stimulation. In fact, multiple experiments researching the evolutionary purpose of boredom have supported an interesting theory – It seems that bored people tap into their creative side more than those who aren’t 👩🎨.

So, could boredom really be the fuel of our imagination?

WHAT DOES BOREDOM DO TO THE BRAIN?

During boredom, we see the activation of areas in the brain linked to negative emotions like fear and disgust. Deakin University’s Professor Peter Enticott describes boredom as a subconscious motivation alarm🚨: “The key here is to think of it like any other negative emotion: it motivates our behavior. It’s a way of keeping us on our toes and aware of what’s going on around us.”

Fancy, huh?

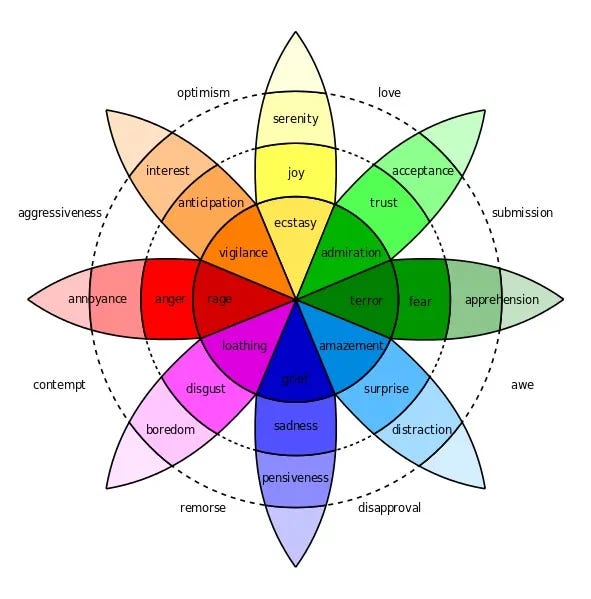

If we take a look at Robert Plutchik’s emotion wheel — where the 8 basic emotions are extended in order of intensity — boredom shows up as a milder version of disgust. So, just like the wave of nausea and disgust you feel when Dave from accounting goes in for a handshake after you’ve seen him skip the sink in the bathroom (🤢), boredom protects you from things that aren’t just stimulating enough.

We also see activity in various parts of the prefrontal cortex, the brain's planning and goal-setting manager. In this case, this activation might indicate a drive to act in ways that change our environment and thus, alleviate the negative state of boredom.

When we’re consciously doing things, we’re engaging the “executive attention network”, a.k.a the parts of the brain that shut down the intrusive thoughts of drunk-texting your ex or jumping off your balcony just-to-see-what-would-happen. By contrast, when our minds wander, we flip over to the “default mode network”, the brain’s standby mode💤. But even when daydreaming, we’re still using about 95 % of the energy that hardcore, focused thinking requires. So despite being in an inattentive state, our brains are still working remarkably hard.

And here’s where things get interesting: daydreaming shares some traits with actual dreaming. Both involve free association of thoughts and a silenced inner critic, allowing unexpected associations to emerge—often leading to some of our most creative ideas 💡.

When we daydream, we see higher activities in brain regions responsible for recalling autobiographical memory (our personal archive of our life experiences), imagining what others are thinking and feeling, conjuring what-if scenarios, and crafting a coherent sense of self. Funny enough, people who've got themselves all figured out, can easily label their feelings and have high levels of self-awareness are way less likely to get bored.

That’s the crux of daydreaming: you replay and reframe experiences from your own inner world, not just the outside world's version. As Prof. Jonathan Smallwood, from Queen’s University, points out: during an argument for instance, your brain is too swamped with anger and adrenaline to be objective. But later, while showering or driving, your brain replays the scene, and suddenly your thoughts align. Not only do you become a genius with all the perfect comebacks 💅, but without the presence of the actual person you might see things from a new angle and gain fresh insights.

It turns out that a propensity for boredom is a sign of a healthy mind. So perhaps we should stop trying so hard to keep tedium at bay, embrace the boredom, and let our thoughts take a walk down memory lane. Who knows, you might even solve the mystery of the missing sock in the laundry 💌…